The Unbelievable Tale of the Woman Who Mooned Her Way Out of the Legal System

Discover the scandalous saga of Gaia Afrania, the audacious Roman matron whose legal antics shook ancient Rome, leading to a ban on female advocates that lasted over 2000 years!

In the bustling heart of the Roman Republic, up until around 50 BCE, women were as free as men to act as legal advocates. Most renown among these legal eagles, there was a woman named Amaesia Sentia. Amaesia was not your ordinary matron; she had a knack for legal banter that earned her the moniker "Androgyne" because everyone thought she must be a man's spirit encased in a woman's body.

The spirit of a man, because although women were allowed to bring cases before the magistrates, the skills of oration, rhetoric, and advocacy were a masculine domain, dominated by men. A man's ability in these areas could make or break his career.

For this reason, many a man, such as Cicero and Julius Caesar, would take up legal advocacy as a way to build their reputation which would aid their climb up the cursus honorum (course of honour).

Enter Gaia Afrania, a woman whose presence in court was as frequent as the togas worn there. Afrania, the wife of Senator Licinius Buccio, was a regular in the courts, outshining many a man with her legal prowess. But unlike the aforementioned Androgyne, Afrania's courtroom style wasn't exactly the toast of Rome.

In Afrania's time, if non-citizens wanted their case heard by a magistrate, they needed a citizen to advocate on their behalf. Those with wealth could afford a famous advocate like Cicero, but those with little to nothing struggled to find anyone at all. Especially if the individual they wished to prosecute or needed defending against was an influential citizen.

Fortunately, for those who didn't mind a female advocate, Afrainia was more than happy to help.

Her litigiousness far surpassed any other woman, and women, according to Juvenal, tended to be quite litigious. So it's fair to say, Afrania was likely in court a lot. And she certainly built up a reputation.

Afrania seemed to have a knack for getting under the skin of men she bested in court and soon her active courtroom presence began to wear thin on the local magistrates. Thus, in a move that could only be described as a display of Roman-sized petulance, an edict was passed, barring not just Afrania but all womankind from advocating on behalf of others. Afrania, in a remarkable feat of victim-blaming, was painted as the villainess behind this loss of rights.

Now, it's fair to wonder: what sort of cases was Afrania taking on? To generate this level of anger and such a draconian reaction, it's fair to speculate that she must have been very successful, and potentially disruptive to the courts, possibly because she brought to trial matters of less importance, thus delaying more "important" matters from being heard.

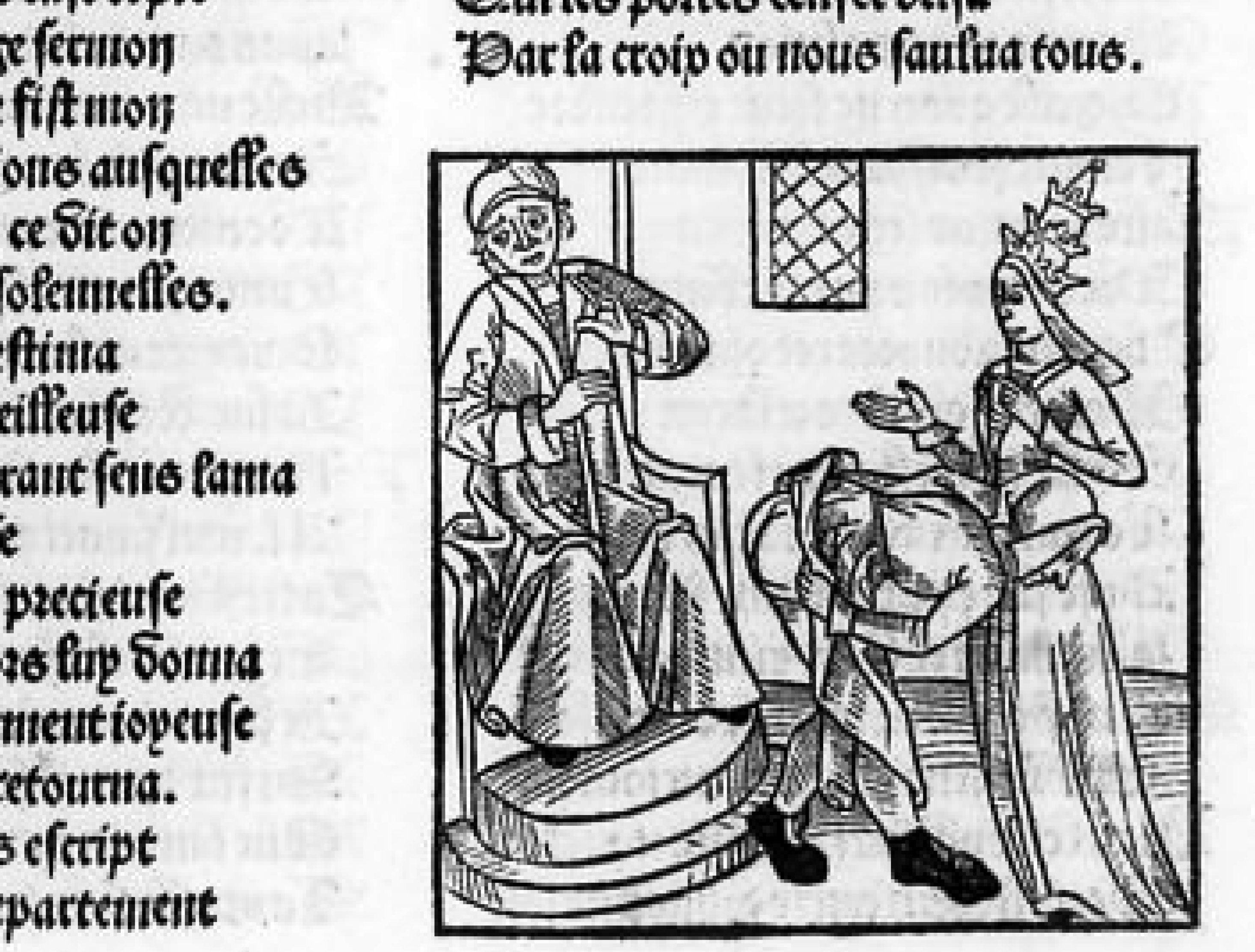

Fast forward to the 2nd-3rd century CE, Roman Jurist Ulpian gives us a little tidbit about Afrania's role in getting women banned from practicing law. This piece of history was preserved in the Digesta, a law codex compiled on the order of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (530–533 CE).

Here's where it gets interesting. Afrania, or Carfania as she came to be known, didn't just vanish from history. She becomes a folk legend, her name mutating as it travelled around Europe, serving as the explanation for why women could not be law advocates.

And then a reason for something even worse. It seems Afrania, who had died in 48 BCE, was still influencing law over 1300 years later, though probably not in the way she had hoped.

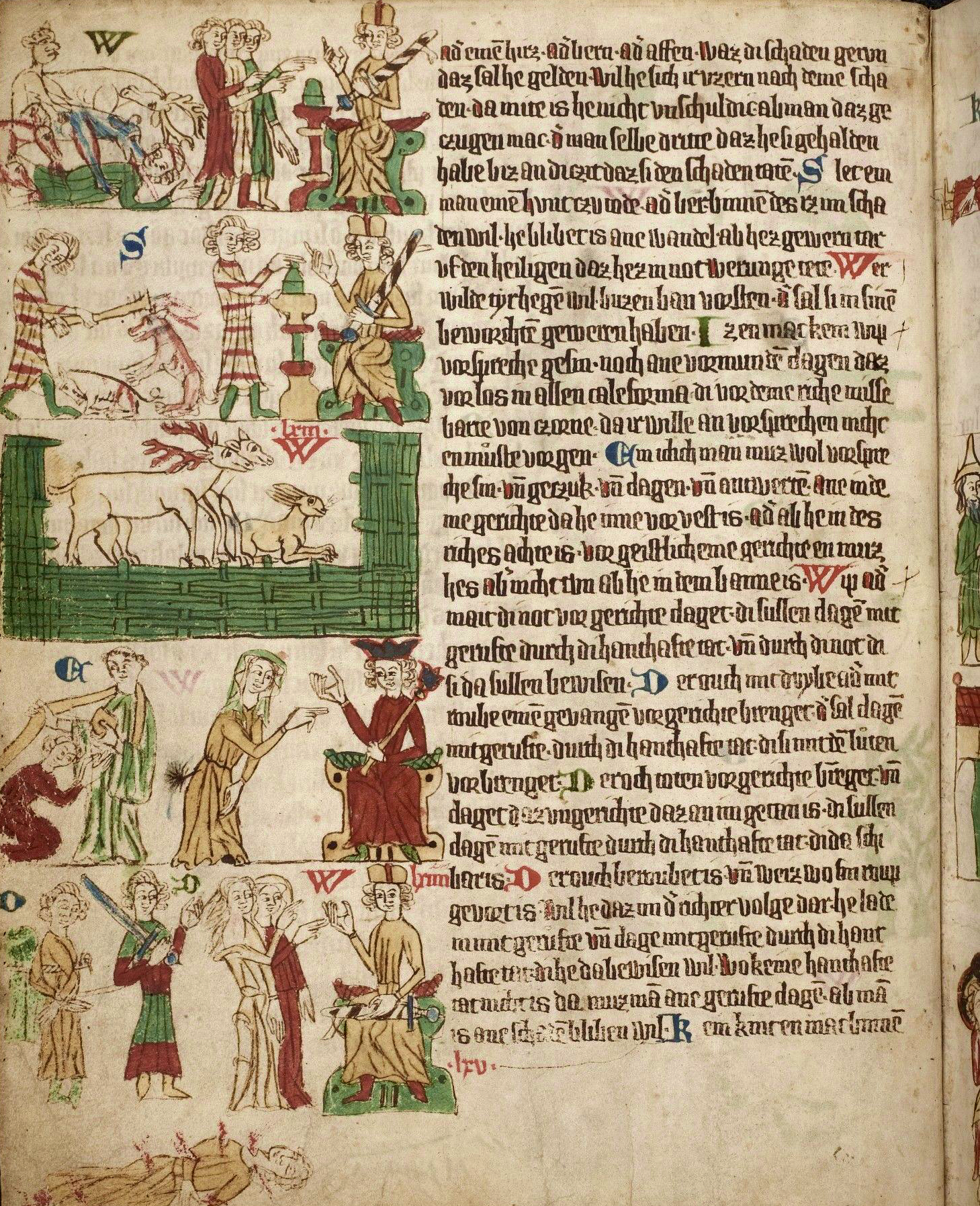

Her story takes a grim turn in 1255. In the most important law book of the Holy Roman Empire, Sachsenspiegel (The Saxon Mirror), Afrania makes a cameo as Calefurnia. The book claims that Calefurnia, in a fit of rage, bared her derriere to Charlemagne, who in response, ordered that women must have a male guardian with them if they were to be in a courtroom.

This 'Calefurnia law' had far-reaching implications. Women lost the right to testify or plead their own innocence, could not report a crime of which they were the victim, and even mothers and midwives couldn't testify about the condition of a newborn without a man present. And who was the scapegoat for this state of affairs? Why, Calefurnia (C. Afrania), of course.

From the courtroom to the birthing room, the impact of C. Afrania's legendary courtroom antics echoed through centuries. Her infamy continued as she became the subject of bawdy poems, obscene doodles,and tall tales that would make even the most shameless gossip blush. Afrania's name became synonymous with a woman without shame, an odd blend of myth, legend, and the occasional dash of humor.

Women wouldn't reclaim the right to advocate until somewhere between the end of the 19th and the middle of the 20th century. So, who do we pin the blame on here? Afrania, for potentially abusing the court system, or the men, for their seemingly fragile egos? Well, no matter how you slice it, it seems the response was, let's say, a bit of an overreaction.

Sources:

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings 8.3, 1st century. CE

Latin:

III. QVAE MVLIERES APVD MAGISTRATVS PRO SE AVT PRO ALIIS CAVSAS EGERVNT

INITIUM. Ne de his quidem feminis tacendum est, quas condicio naturae et uerecundia stolae ut in foro et iudiciis tacerent cohibere non ualuit.

EXEMPLUM 1. Amesia Sentinas rea causam suam L. Titio praetore iudicium cogente maximo populi concursu egit modosque omnes ac numeros defensionis non solum diligenter, sed etiam fortiter executa, et prima actione et paene cunctis sententiis liberata est. quam, quia sub specie feminae uirilem animum gerebat, Androgynen appellabant.

EXEMPLUM 2. C. Afrania uero Licinii Bucconis senatoris uxor prompta ad lites contrahendas pro se semper apud praetorem uerba fecit, non quod aduocatis deficiebatur, sed quod inpudentia abundabat. itaque inusitatis foro latratibus adsidue tribunalia exercendo muliebris calumniae notissimum exemplum euasit, adeo ut pro crimine inprobis feminarum moribus C. Afraniae nomen obiciatur. prorogauit autem spiritum suum ad C. Caesarem iterum <P.> Seruilium consules: tale enim monstrum magis quo tempore extinctum quam quo sit ortum memoriae tradendum est.

English:

III. Of Women that pleaded Cases before Magistrates

We must be silent no longer about those women whom neither the condition of their nature nor the cloak of modesty could keep silent in the Forum or the courts.

Example 1. Amesia Sentia, a defendant, plead her case before a great crowd of people and Lucius Titius, the praetor [77 BCE] who presided over the court. She pursued every aspect of her defence diligently and boldly, and was acquitted, almost unanimously, in a single hearing. Because she bore a man's spirit under the appearance of a woman, they called her Androgyne.

Example 2. Gaia Afrania, the wife of the senator Licinius Buccio, a woman disposed to bringing suits, always represented herself before the praetor: not because she had no advocates, but because her impudence was abundant. And so, by constantly plaguing the tribunals with such barking as the Forum had seldom heard, she became the best known example of women's litigiousness. As a result, to charge a woman with low morals, it is enough to call her 'Gaia Afrania'. She prolonged her life until Caesar's second consulship with Publius Servius [48 bce] as his colleague; for it is better to record when such a monster died than when it was born.

DIGESTA, 3.1.1.5

Ulpianus, On the Edict, Book VI.

Latin:

Secundo loco edictum proponitur in eos, qui pro aliis ne postulent: in quo edicto excepit praetor sexum et casum, item notavit personas in turpitudine notabiles.

sexum: dum feminas prohibet pro aliis postulare. et ratio quidem prohibendi, ne contra pudicitiam sexui congruentem alienis causis se immisceant, ne virilibus officiis fungantur mulieres: origo vero introducta est a carfania improbissima femina, quae inverecunde postulans et magistratum inquietans causam dedit edicto.

English:

The following edict regards those who may not advocate on behalf of others. In this edict the praetor debarred on grounds of sex and disability. He also blacklisted people known to be disreputable.

Regarding sex: he forbids women to advocate on behalf of others. The reason for this prohibition is to prevent them from involving themselves in the cases of other people contrary to the modesty in keeping with their sex and to prevent women from performing the functions of men. Its introduction goes back to a most infamous woman called Carfania who's shameless advocating annoyed the magistrate and gave rise to the edict.

Juvenal on women in general, Satire 6, excepts. Rome 2nd cent. AD.

"There's hardly a case in court where the litigation wasn't begun by a female. If Manilia can't be defendant, she'll be the plaintiff."

A. E. Sokol, California: A Possible Derivation of the Name. California Historical Society Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 1 (Mar., 1949), pp. 23-30

Madeline H. CAVINESS, Women and Minorities in Sachsenspiegel Transactions of the Japan Academy, Vol. 72, Special Issue